Double jeopardy for survivors of domestic violence, child abuse, and sexual assault

Why federal funding for support organizations is a matter of life and death

We usually think of double jeopardy as a legal term that prevents Americans from being convicted for the same crime twice. But the phrase also describes the ominous reality faced by abuse survivors whose support systems may be interrupted or discontinued—leaving them doubly vulnerable to perpetrators who are emboldened by conditions that isolate or demoralize.

The threat of re-victimization is real.

Regional and national domestic abuse support providers such as The Hotline, The Safe Alliance, Violence Free Minnesota, the Ion Center for Violence Prevention (among hundreds of others across the U.S.) can take little comfort in the temporary pause on the federal freeze. Orgs are planning now for worst-case scenarios if funding is gutted—federal grants stabilizing total budgets range from 30% to 90%—and in a time when personal philanthropy is down.

Why do these organizations matter? Until the early 1970s, there were few if any supports for victims to turn to outside their own personal networks. This meant that it was much harder for individuals to find external validation, guidance, or safe harbor when experiencing physical or psychological abuse behind closed doors.

Since that decade, community support providers have become essential for ensuring abuse education and prevention, providing hotline support, outreach, legal resources, counseling, medical treatment, and shelter. Many also now conduct and share research, preserve records, report and monitor trends, and contribute vital expertise and training for law enforcement and other professionals.

Before hotlines or safehouses existed, a survivor might dare turn to friends, parents, extended family, police, doctors, teachers, or clergy for support. Maybe those folks understood what abuse looked like and knew what to do. Maybe they were themselves perpetrators. Maybe allies thought the answer was simple—“Just leave”— not knowing that leaving itself is the most perilous time for survivors.

Before hotlines and safehouses existed, kids facing parental violence would be told to behave better and stop being so difficult. Children and youth shocked by the horror of sexual abuse at church would be told they were going to hell for lying about clergy. White women who spoke the truth about violent or sexually coercive partners would be lectured on the benefits of making a tastier dinner or not going to bed with curlers in their hair. People in communities already targeted or marginalized—Black, Latinx, and Indigenous folks; immigrants; religious minorities; LGBTQ Americans; people living under severe economic stress—suffered extra pressure to avoid calling potentially “negative” attention to themselves or their loved ones, no matter how severe the abuse was.

Survivors’ personal contexts of abuse—from ethnicity and language to gender and sexual identity, age, geographic location, and much more—have made culturally informed education, outreach, and support essential. But now, as providers brace for drastic financial impact pending the pause on the federal freeze, some are pre-emptively scrubbing or adjusting website content for any language that could be targeted as “DEI.”

The material stakes are outrageously high in 2025. And abuse thrives under conditions of confusion, disorientation, and misdirection—in a relationship, in a household, under a sacred steeple, or in the halls of highest government. Budgetary uncertainty has grimly re-perpetrated these conditions on a national scale for the very organizations dedicated to providing lifelines of validation, clarity, and security to survivor-victims and their loved ones.

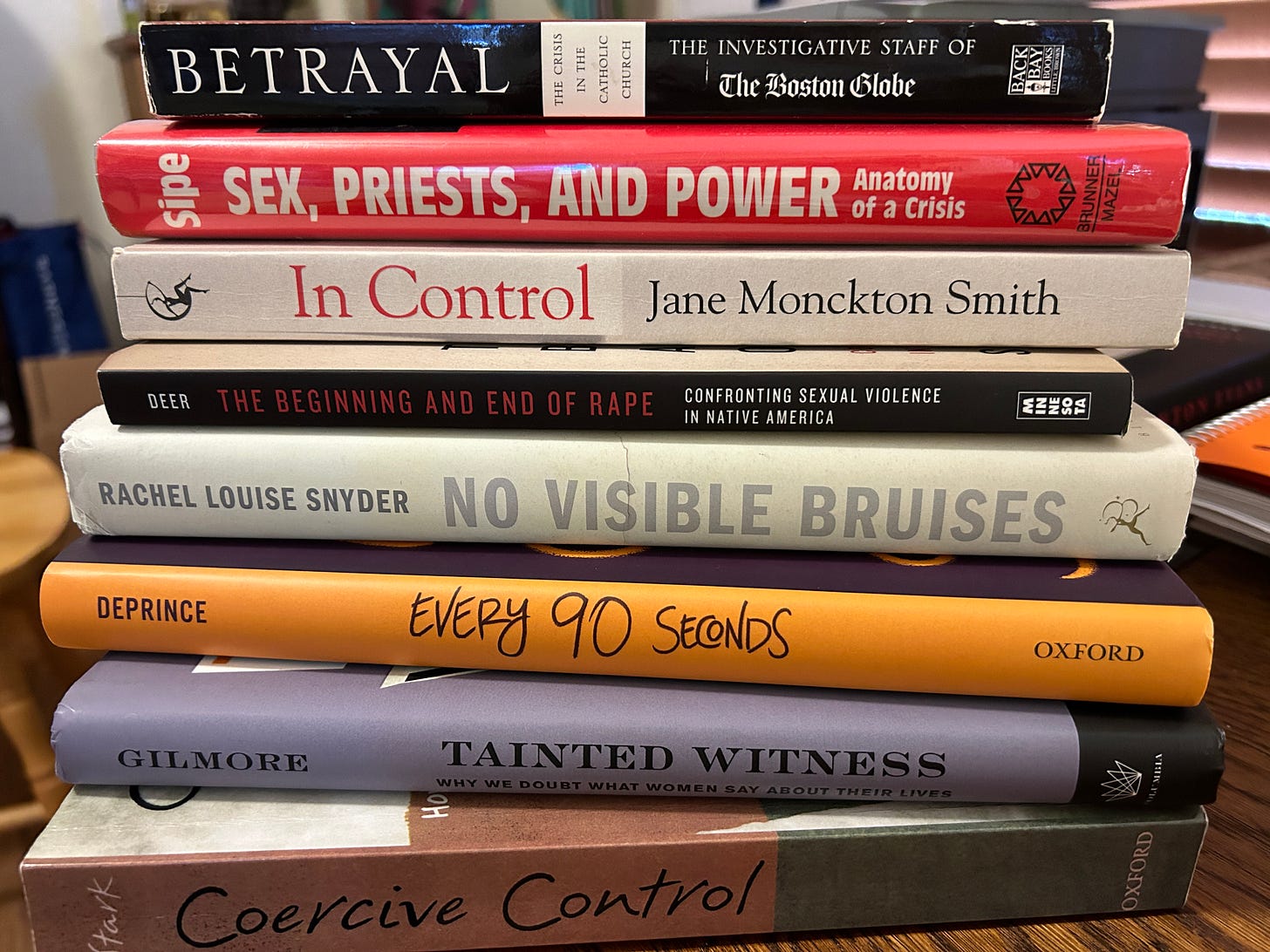

“A web of control can also include the knowing or unknowing collusion of others.” Jane Monckton Smith, In Control: Dangerous Relationships and How They End in Murder

How do disorientation and confusion contribute to abuse? I have spent much of my writing career working to document and untangle variations of that experience. What has become increasingly clear to me in case after case is that, whoever they are and wherever they come from, abusive individuals learn how to exploit the conscientiousness of decent and well-meaning people.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but abusers are highly adept at appealing to and manipulating rules while perpetrating their behavior. Their only real rule, spoken or unspoken, is “because I say so,” thereby subjugating any external standards of behavior to their own whim and exempting themselves from mutual accountability. In casual speech, we just call this “moving the goalposts.”

On this theme, I want to conclude with an unfortunately timely audio excerpt from my book, MASS: A Sniper, a Father, and a Priest (Pelekinesis), which received a silver medal for biography in the 2020 eLit Awards. An abridged version of this selection appeared in Issue 10 of Tahoma Literary Review and later received a Pushcart Special Mention in 2019.

CW: domestic violence, family violence

Abuse can happen to you, or to anyone. We must not return to the days when victim support and survival in America was a lethal game of chance. More than five decades of life-changing research, education, advocacy, and organization have made futures without abuse possible for countless people—yet there is much that remains to be done.

DV and IPV organizations must be assured of continued federal support. To threaten anyone dedicated to this work is to threaten survivors everywhere.

xo

Jo

So glad to see you on Substack, Jo. Thank you for your continued advocacy. I look forward to reading and keep up here!